|

| The moment had arrived! Seeing Bottger's highlighted teapot (far left, second shelf) was golden! |

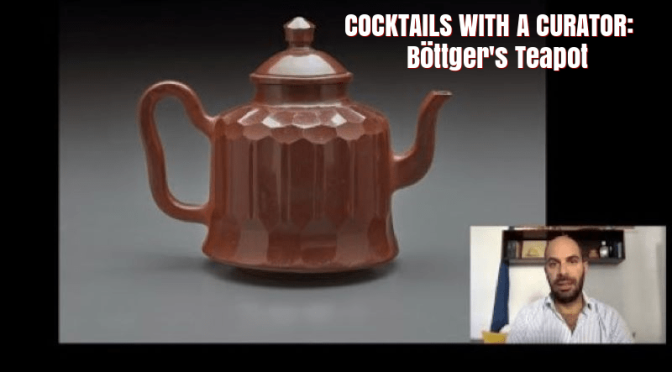

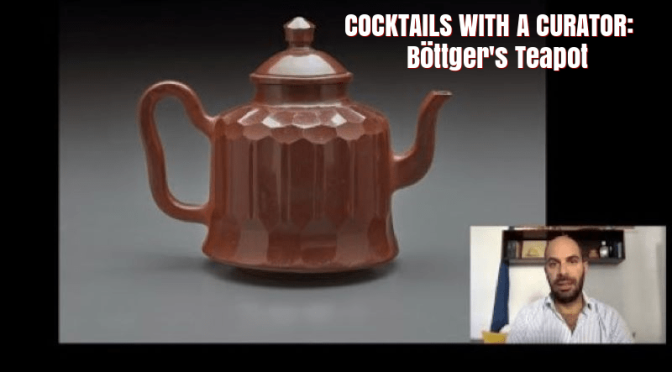

During the height of quarantine in 2020, the Frick Museum launched a weekly video series titled Cocktails with the Curator, where a museum expert would present a curated object—be it a painting, clock, or ceramic—paired with a themed drink. My favorite episode, which I replayed like a Casey Kasem chart-topper, was Böttger’s Teapot, a riveting dive into Europe’s first successful attempts to replicate Chinese porcelain. As tea, coffee, and chocolate swept into western Europe in the 17th century, so, too, did the desire for elegant serving ware among the royals and aristocracy.

In our BTS blog, Böttger’s Teapot, Cocktails, Mocktails and the History of European Porcelain from the Frick Museum (February 2021), we shared the remarkable story of Johann Friedrich Böttger. Born in Germany in 1682, Böttger began in his family’s trade of coin minting before spinning tales that he was an alchemist capable of transforming base metals into gold—a claim that piqued the interest of European royals, starting with Frederick of Prussia. When the illusion couldn’t hold, Böttger fled to Dresden, only to be captured by Augustus the Strong, who also hoped to cash in on Böttger’s miraculous promises.

|

| Cocktails with Curator, much watched episode, Bottger's Teapot |

A fellow prisoner, Ehrenfried Walter von Tschirnhaus, was already experimenting with replicating Chinese porcelain, and it was here that Böttger pivoted—abandoning alchemy and embracing the chemistry of ceramics. After many trials using kaolin, red clay, and feldspar, Böttger produced stoneware—close, but not quite porcelain. A few years later, he finally struck the right combination for white porcelain.

As noted in our May BTS blog, Treasures from Holland: Windmills, Delft and Wooden Shoes, the Dutch had long admired Chinese porcelain and attempted their own interpretations in Delft. However, without kaolin, their ceramics were less durable and of lower quality. Once kaolin deposits were discovered in England and other parts of Europe, demand for Delftware declined.

|

| Portico Gallery includes many ceramics |

|

| . . . and other fancy servingware |

Still, Böttger’s red stoneware stood out for its beauty. It could be polished or left matte, and many of his works combine both finishes. Several pieces are now housed in the Frick’s collection—including that dazzling 2020 centerpiece, Böttger’s Teapot.

|

| BTS were quick to purchase tickets. |

|

| The Frick reopened April, 2025 after renovations. |

This April, good fortune came to us as Frick reopened its doors after an almost five-year renovation, and our BTS crew were quick to book tickets for our New York visit. Last week, I stood face-to-face—or more accurately, face-to-pottery—with Böttger’s teapot. It felt like attending an all-star concert of one of America’s Top 40: all the fanfare, none of the noise.

|

| Bottger's teapot, rock star status for red stoneware! |

Located in the portico gallery just off the Frick's library, Böttger’s porcelain is part of a hallway lined with exquisite ceramics and serving ware. Seeing this diminutive teapot in person—and its stoneware companions—was nothing short of a golden opportunity.

4 comments:

What a cool story! I had no idea about this rock-star teapot!

Thanks, Clay! It really was pretty remarkable to finally see it!

Great post and lovely photos. Warm greetings from Montreal!

Hello Linda! Thank you and great to hear from you! We were in Montreal last year (and Sorel), tracing family roots and seeing the sites (wrote about it in two blog stories, August 2024). Loved "Old Town"!. Last time we were in the area was Expo '67, so we were long overdue for a return visit. :) We plan to be back next year. (hoping to squeeze in an afternoon tea, too!).

Post a Comment